Nematodirus

About Nematodirus

Grazing lambs are commonly affected by a number of different parasitic gutworms that live in their stomach and intestines. One of these gutworms is Nematodirus battus (sometimes called thread-necked worm). This worm typically infects young lambs in spring at around 6-8 weeks of age.

How do Nemotodirus impact the health of your animals?

Signs of infection include reduced appetite, reduced production, acute yellow/green diarrhoea and subsequent dehydration. The lamb fleece can also appear dull or rough and infected animals could be displaying abdominal pain with a “tucked-up” appearance and sunken eyes.

Infective larvae are ingested with grass and find their way to the small intestine where they disrupt the normal integrity, structure and function of a lamb’s small intestine, leading to the disease symptoms described above. Intensity of the infection varies between lambs. Whilst the majority will recover within a month, mortality rates can be as high as 10-30% of the lamb crop in which animals suffer intense scouring and succumb to dehydration quickly.

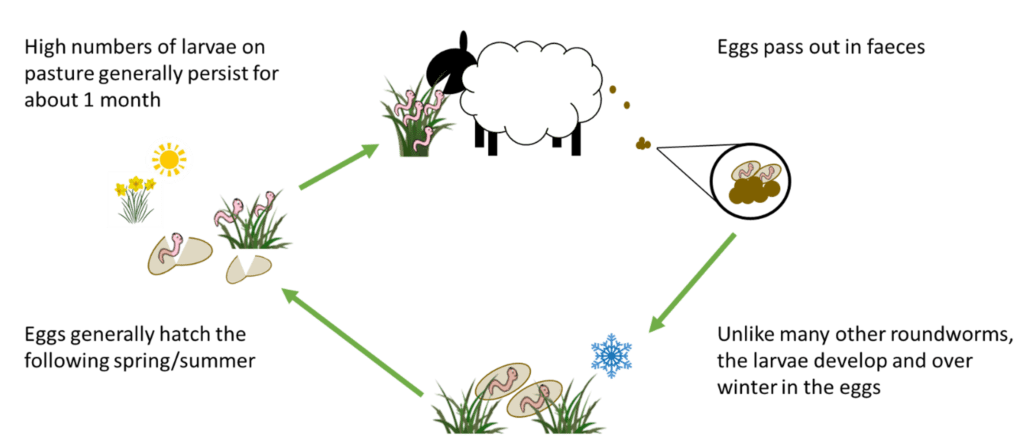

Villi (finger like projections that increase the surface are of the gut) allow nutrients and water to taken up by the body. Nematodirus bind these villi together stopping the host from effectively taking up nutrients (leading to poor growth) and water (leading to dehydration).

The image below shows part of a Nematodirus coiled around three villi, binding them together:

![]()

Lamb infections in spring

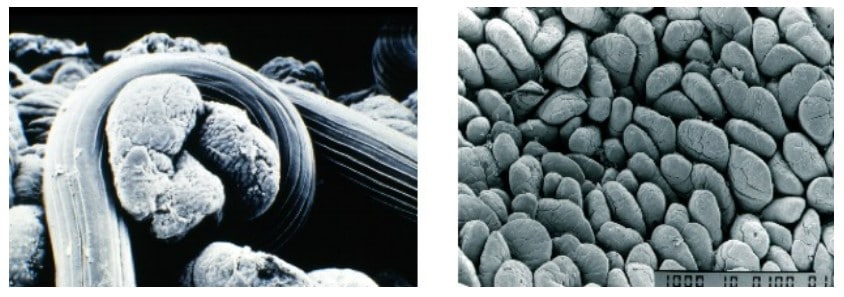

Disease generally occurs when lambs graze on contaminated pasture at the same time as mass Nematodirus egg hatch.

The main symptoms are:

- Profuse, watery yellowy-green diarrhoea leading to dehydration

- Reduced appetite & productivity

- Dull/rough fleece and a “tucked-up” appearance.

Diagnosis

Disease can occur rapidly with lamb deaths occurring before parasite eggs appear in faeces therefore faecal egg counts (FEC) are not recommended for diagnosing Nematodirus. But FEC can be useful to determine if other agents are causing scour e.g. coccidia. Use the Nematodirus forecast link below to find the high risk period for your area and closely monitor lambs for signs of disease.

Nematodirus forecast

Predicts the hatch risk for Nematodirus eggs based on weather/climatic data in 140 locations throughout the UK. You can view this at: www.scops.org.uk/nematodirusforecast

Control

White drenches (1-BZ) are recommended. Alternative control strategy: Where possible, avoid grazing young lambs on the same fields each spring to reduce pasture infection.

White drench resistance

Resistance in Nematodirus is currently at low levels in the UK. White drenches (1-BZ) still expected to be effective for the control of Nematodirus in lambs in spring on the majority of farms. To check treatment worked, conduct faecal egg counts 7-10 days post-treatment.

Autumn infection

Outbreaks of the disease have been seen in older lambs later in the grazing season.

Acute disease can be difficult to diagnose as severe clinical symptoms, and even lamb deaths, can occur before worm eggs appear in the faeces of infected animals. Faecal egg counts are therefore not a reliable indicator of when to treat for Nematodirus.

Acute disease can be difficult to diagnose as severe clinical symptoms, and even lamb deaths, can occur before worm eggs appear in the faeces of infected animals. Faecal egg counts are therefore not a reliable indicator of when to treat for Nematodirus.

Monitor the Nematodirus forecast on the SCOPS website (https://www.scops.org.uk/forecasts/nematodirus-forecast/). Find the weather station closest to your farm in location and altitude on the map and check regularly to see when the risk changes from low to high.

The forecast predicts the hatch date for Nematodirus eggs based on temperature and climate data from 140 weather stations throughout the UK and should be used in combination with your grazing history to assess the risk of infection in lambs.

SCOPS advice:

If your lambs are grazing pasture that carried lambs last spring and you answer yes to one or more of these questions, your lambs are at risk:

Are they old enough to be eating significant amounts of grass? (generally 6-12 weeks of age but may be younger if ewes are not milking well)

Do you have groups where there is also likely to be a challenge from coccidiosis? For example, mixed aged lambs are a higher risk

Has there been a sudden, cold snap recently followed by a period of warm weather?

Have you got lambs that are under other stresses e.g. triplets, fostered, on young or older ewes.

Recommended actions

If possible, avoid infection. Move at-risk lambs (as determined by the risk assessment) to low risk pastures (i.e. pasture that was not grazed by lambs the previous spring).

If you cannot avoid high risk pasture grazed by lambs the previous spring and decide you need to treat for nematodirus, SCOPS advises farmers to use a white (1-BZ) drench. Use the SCOPS ‘Know Your Anthelmintics’ Guide to select a product. These are still highly effective against this parasite on most farms and suitable for young lambs.

Check that treatment is effective by taking a FEC seven to 10 days after treatment. Remember, it may be necessary to treat lambs more than once depending on the spread of ages in a group and subsequent weather conditions.

White drenches have been recommended for treatment of Nematodirus infection for around 60 years. Despite repeated use of this drug, resistance was not identified in Nematodirus battus until 2010. Genetic tests can be used to look for mutations linked with white drench resistance in this gutworm. A study was conducted by Moredun to explore how common the mutations associated with white drench resistance are within N. battus populations collected from UK sheep flocks.

The main genetic mutation associated with resistance to white drenches (F200Y), was identified on around one in four of farms tested. The mutation was found to be at a low level in the majority of cases but there were some farms where resistance was at a high level. On average 2% of the N. battus worms examined carried the mutation. A second mutation (F167Y) that is also associated with white drench resistance was identified on a small number of farms in the UK but at a very low frequency (~1% of worms examined).

The results suggest that white drench resistance is at a very early stage in Nematodirus in the UK. The finding of the genetic mutations associated with resistance on over a quarter of the farms means that this figure could increase in the future; however, these drugs will still be effective against Nematodirus in spring on the majority of farms.

To test whether white drenches are working against Nematodirus on your farm, faecal egg counts can be done 7-10 days after treatment.

Beware! Whilst a reduction in Nematodirus eggs in the post-treatment egg count could indicate that the drench was effective, it could also be due to the lamb’s natural immunity kicking in and reducing egg output from adult worms. However, if large numbers of eggs are present in the post-treatment egg count, this could possibly indicate that the drench was not effective.

Other anthelmintic classes are effective against Nematodirus. However, it is necessary to checks labels to ensure they have a label claim. Also, the use of white drenches in spring is likely to safeguard the other drug classes for use later in the season against other gutworm species.

Related publications

Nematodirus is typically a spring infection in young lambs and this is still when the majority of acute disease is observed. However, in recent years, the behaviour of this worm appears to be changing and is now regularly observed outwith spring.

Historical perception of seasonal Nematodirus infection compared with recent observations.

Typical spring infection

Eggs from the previous year’s lamb crop have over-wintered on pasture and undergo a mass hatch when warm temperatures stabilise in spring; eggs have experienced a chill followed by an average day/night temperature of greater than 10°C for 10 consecutive days. Acute disease occurs when the mass hatching of eggs into infective larvae coincides with the grazing of young lambs.

Hatching at different times of year

Changes in climate and parasite behaviour are factors that are believed to have led to a second hatching event in autumn on some farms. A recent study conducted by Moredun found that 50% of the surveyed farms observed Nematodirus out-with spring, 15% of which experienced disease in autumn and 3% in winter. Surveillance data showing lab detections of Nematodirus battus from the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA; below) also highlights a peak in autumn, particularly in those samples collected from the South of England and Wales.

A recent study into egg hatching behaviour suggested that some eggs no longer required a period of chilling before they hatch. Those eggs would not have to be exposed to winter temperatures before hatching and could hatch in autumn when temperatures are similar to spring, possibly allowing for two generations of the worm within a single year.

Animal and Plant Health Agency Nematodirus surveillance data for England and Wales January 2015/December 2017. Lab detections of Nematodirus throughout the year in the North (North England) and South (South England and Wales). The lines represent the number of Nematodirus positive submissions in the South (red) and North (black). The bars represent the mean Nematodirus faecal egg count of samples submitted per month (overall average, not split by region).

Which animals are at risk of autumn infection?

Any animals which have not been previously exposed to Nematodirus will be at a greater risk of developing disease in autumn, e.g. lambs which did not receive a moderate/high challenge in spring. These may be lambs which were grazed on clean pasture or where spring hatch was interrupted by fluctuating temperatures.

We are looking at farm management practices and environmental conditions which may act as risk factors, increasing the likelihood of either white drench resistance developing or changes in the behaviour of Nematodirus on farm.

In a separate project we are also exploring gutworm transmission between farms through animal trade with a view to quantify the risk and ensure quarantine recommendations are up to date.